Haifa, some History

Haifa in the Middle Ages 640-1291

1100 Haifa conquered by the Crusaders

The eras of the Mamelukes and the Ottomans 1291-1918

1799 Taken by Napoleon

1839 Captured by Egypt 1839;

1840 Conquered by Turkey 1840;

1918 Taken by the British 1918

1799 Taken by Napoleon

1839 Captured by Egypt 1839;

1840 Conquered by Turkey 1840;

1918 Taken by the British 1918

Haifa during the British Mandate period 1918-1948

1922 Palestine mandate

Temples, mosques, churches in Haifa

I.N.A. videos

1922 Palestine mandate

Temples, mosques, churches in Haifa

I.N.A. videos

Pythagoras

M. Michaud Correspondance d'Orient

L Janet Jerusalem et la Terre Sainte

Leonie de Bazelaire Chevauchee en Palestine

L Janet Jerusalem et la Terre Sainte

Leonie de Bazelaire Chevauchee en Palestine

Doubdan Akko, Naaman and Kishon rivers , Carmel mount and Haifa

Shikmona potteries and mosaics

| . |

| . |

The Atlit bronze ram

National Maritime Museum

National Maritime Museum

Theodore Herzl

Nazareth and Tiberias

Baybars Kuran (British Library)

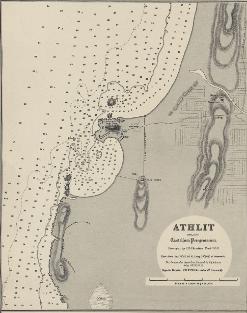

Atlit Bay Castel Pellerin

Caesarea

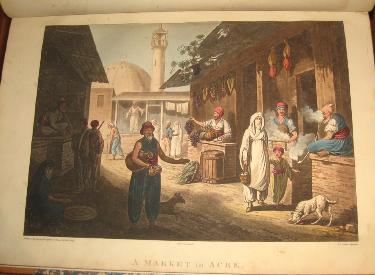

Spilsbury, Acre market

Alexander the Great, Tel Dor

At the Meggido battle, the Turcs are

defeated by the troops of General Allenby.

End of the Ottoman period

WWI next to Haifa, ANZAC

defeated by the troops of General Allenby.

End of the Ottoman period

WWI next to Haifa, ANZAC

Illegal immigrants camp , Atlit

Exodus

From The History of the Jewish People

1100 July 25, HAIFA (Eretz Israel)

Jewish residents joined with the Fatimids of Egypt in defending the city. Tancred, who unsuccessfully attacked Haifa, was

reprimanded for his lack of success and told that he made "a mockery of the God of the Christians." Once the city fell, the

remaining Jews were massacred by the crusading forces.

1109 TIBERIAS (Eretz Israel)

Fell to the Crusaders. As a rule, once the military conquest ended the Jewish inhabitants were left alone. The notable

exceptions were Haifa and Jerusalem (see 1099).

1799 March 18, HAIFA WAS CAPTURED BY NAPOLEON

This marked the greatest extent of Napoleon's conquest of Eretz Israel. The next day the French reached Acre. It was

successfully defended by both British warships and local towns people, including the Jewish inhabitants. By June, Napoleon

gave up and returned to Egypt.

1824 - 1904 KALONYMUS ZE'EV WISSOTZKY (Russia)

Merchant and philanthropist. Wissotzky was one of the earliest supporters of the Zionist movement. He established a

successful tea house which still bears his name. Upon his death, he left his share of the business (one million Rubles) to

charity, part of which went to found the Technion in Haifa.

1907 ERETZ ISRAEL

Ten years after the first Zionist Congress there were approximately 80,000 Jewish inhabitants in Eretz Israel: 45,000 in

Jerusalem, 8000 in Jaffa, 8000 in Safed, 2000 in Haifa, 2000 in Tiberias, and 1000 in Hebron. In addition, there were 14,000

people living in over 30 villages and underdeveloped land.

1908 January 7, PALESTINE LAND DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY

Was established. Later known as the Israel Land Development Authority (ILDC), the authority was in charge of purchasing

and cultivating land for the Jewish National Fund and for private individuals. Its first Chairman was Otto Warburg and its

first director Arthur Ruppin. The company was instrumental in establishing settlements such as Nahalal, Tel Yosef, Ein

Harod, and the first kibbutz, Degania. Many of its purchases were in the Sharon Plain, and the Hula valley. They also played

a major role in developing Tel Aviv and the Hadar Carmel section of Haifa.

1912 April 11, HAIFA (Eretz Israel)

The Technikum, later to be known as the Technion, was founded. In 1913 the Hilfsverein der Deutschen Juden (Ezra), which

established the Haifa Technion, was struck by both teachers and students when they tried to institute German as the school's

language instead of Hebrew. The American co-trustees agreed with the strikers and the Society left Eretz Israel after the First

World War. Due to both the strike and the approaching war the school did not actually begin classes until 1924.

1915 April, ERETZ ISRAEL - NILI (Hebrew initials for Netzah Israel Lo Yeshaker)

Was organized by Avshalom Feinberg and Aaron Aaronsohn to spy against the Turks for the British. Based in Zichron Yaakov

and locally run by Aaronsohn's sister Sarah, they passed messages regarding Turkish troop maneuvers around the Haifa area.

In 1917 the Turks broke the spy ring. Sarah was arrested October 1, and after being tortured for three days, managed to

commit suicide. Most of the other members were captured and killed.

1916 May 16, SYKES-PICOT AGREEMENT

France and Britain (with the agreement of Russia) divided up the Ottoman Empire. France was assured of Lebanon, Syria

and Northern Iraq, and Britain was given control of Northern Arabia, Central Mesopotamia (Iraq), and much of the Western

Persian Gulf. Russia also received some Armenian and Kurdish territory. Eretz Israel was divided, with France controlling the

Galilee, Britain the Haifa area, and the rest of the country under international control.

1918 September 23, Haifa was captured by the Mysore and Jodhpur Lancers, British and Commonwealth troops. Many

soldiers are buried in Haifa cimetries

1920 January 4, METULLA (Eretz Israel)

Bedouin attacks on the north forced the French at a fort near Metulla to retreat. The 120 members of the settlement were

forced to flee to Sidon, where they boarded a ship to Haifa.

1925 February 10, THE TECHNION (The Israel Institute of Technology) (Eretz Israel)

Was opened in Haifa, making it the first institute of higher education to be opened in Eretz Israel. Its first head was Shlomo

Kaplansky whose goal was to train engineers to the highest of European standards. By 1952 the Technion was offering

Masters and Doctorates. Today the Technion remains Israel's main training center for its high tech industries.

1940 November 25, SINKING OF THE PATRIA (Haifa, Eretz Israel)

In Haifa harbor. The French refugee ship, the Patria carried 1,771 "illegal" immigrants. The British decided to add

otherillegals and deport them all to Mauritius, a British colony east of Madagascar. To prevent this move, members of the

Haganah decided to disable the ship. Unfortunately, the explosive charge was too large or the hull was too weak, and the ship

sunk, drowning 257 people. The survivors were allowed to remain in Eretz Israel and were interned for a while at the Athlit

detention camp near Haifa.

1940 June 10, ITALY DECLARED WAR ON GREAT BRITAIN AND FRANCE

A month later, the Italian air forces began bombing Haifa and Tel Aviv. Almost 200 people were killed with hundreds

wounded.

1941 June 12, LUFTWAFFE BOMBED TEL AVIV AND HAIFA (Eretz Israel)

Twelve people were killed in a Tel Aviv old age home.

1944 February 1, IRGUN ZVAI LEUMI (Eretz-Israel)

Began its revolt against British rule. The two limitations it set for itself was not to attack military targets until the end of the

war and not to attack individuals. On February 12, they attacked the British immigration offices in Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, and

Haifa.

1945 November 1, NIGHT OF THE RAILWAYS (Eretz Israel)

In the first cooperative effort between the Haganah, Etzel, and Lehi, railroad tracks all over the country were blown up. This

unification was known as Tnuat HaMeri HaIvri (The Hebrew (Jewish) Resistance Movement. The Haganah sabotaged

railway tracks in 153 places throughout the country, as well as targets in Jaffa and Haifa ports. The Irgun-Lehi unit,

commanded by Eitan Livni, attacked the main railway station at Lydda (Lod). The movement included two representatives of

the Haganah (Yisrael Galili and Moshe Sneh), an Irgun delegate (Menahem Begin) and a Lehi delegate (Nathan Yellin-Mor).

All operations were authorized by the Haganah command, which had the right of veto based on strategic, or political

considerations.

1947 March 31, HAIFA OIL REFINERY (Eretz Israel)

Was severely damaged by Lehi fighters.

1947 July 18, EXODUS 1947 (Eretz Israel)

Was towed to Haifa. The refugees were forced off the boat into three other boats. The Exodus (originally the President

Warfield) carried 4,500 survivors and was stopped at sea by the British Navy. During the struggle, a number of Jews were

killed. The Exodus was destined to become the symbol for all Jews prevented from being able to leave the slaughterhouse of

Europe and immigrate to Israel.

1947 December 29, HAIFA (Eretz Israel)

Arabs attacked Jewish workers at the oil refinery in Haifa, 39 were killed. Two days later, the Haganah attacked the village of

Balad a Sheich in a retaliatory raid.

1948 April 23, HAIFA CAPTURED (Eretz Israel)

By the Haganah. Although loudspeakers called on the Arabs to stay, they fled in mass, urged to do so by leaders of the Arab

High Command. Many of these leaders believed that the upcoming war would be helped by masses of Arab refugees whose

presence would encourage them to join in the attack. The refugees were promised that they would only be away for a short

time and would be able to return when the attacking armies "drive the Jews into the sea". They were also promised

compensation for their property.

1948 April 28, IRGUN ATTACKED HAIFA (Eretz Israel)

After its initial success at capturing the Menasiya quarter, the British prevented the Irgun from continuing. At the same time

the Haganah began Operation Chometz (unleavened bread) to take the areas around the city.

1100 July 25, HAIFA (Eretz Israel)

Jewish residents joined with the Fatimids of Egypt in defending the city. Tancred, who unsuccessfully attacked Haifa, was

reprimanded for his lack of success and told that he made "a mockery of the God of the Christians." Once the city fell, the

remaining Jews were massacred by the crusading forces.

1109 TIBERIAS (Eretz Israel)

Fell to the Crusaders. As a rule, once the military conquest ended the Jewish inhabitants were left alone. The notable

exceptions were Haifa and Jerusalem (see 1099).

1799 March 18, HAIFA WAS CAPTURED BY NAPOLEON

This marked the greatest extent of Napoleon's conquest of Eretz Israel. The next day the French reached Acre. It was

successfully defended by both British warships and local towns people, including the Jewish inhabitants. By June, Napoleon

gave up and returned to Egypt.

1824 - 1904 KALONYMUS ZE'EV WISSOTZKY (Russia)

Merchant and philanthropist. Wissotzky was one of the earliest supporters of the Zionist movement. He established a

successful tea house which still bears his name. Upon his death, he left his share of the business (one million Rubles) to

charity, part of which went to found the Technion in Haifa.

1907 ERETZ ISRAEL

Ten years after the first Zionist Congress there were approximately 80,000 Jewish inhabitants in Eretz Israel: 45,000 in

Jerusalem, 8000 in Jaffa, 8000 in Safed, 2000 in Haifa, 2000 in Tiberias, and 1000 in Hebron. In addition, there were 14,000

people living in over 30 villages and underdeveloped land.

1908 January 7, PALESTINE LAND DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY

Was established. Later known as the Israel Land Development Authority (ILDC), the authority was in charge of purchasing

and cultivating land for the Jewish National Fund and for private individuals. Its first Chairman was Otto Warburg and its

first director Arthur Ruppin. The company was instrumental in establishing settlements such as Nahalal, Tel Yosef, Ein

Harod, and the first kibbutz, Degania. Many of its purchases were in the Sharon Plain, and the Hula valley. They also played

a major role in developing Tel Aviv and the Hadar Carmel section of Haifa.

1912 April 11, HAIFA (Eretz Israel)

The Technikum, later to be known as the Technion, was founded. In 1913 the Hilfsverein der Deutschen Juden (Ezra), which

established the Haifa Technion, was struck by both teachers and students when they tried to institute German as the school's

language instead of Hebrew. The American co-trustees agreed with the strikers and the Society left Eretz Israel after the First

World War. Due to both the strike and the approaching war the school did not actually begin classes until 1924.

1915 April, ERETZ ISRAEL - NILI (Hebrew initials for Netzah Israel Lo Yeshaker)

Was organized by Avshalom Feinberg and Aaron Aaronsohn to spy against the Turks for the British. Based in Zichron Yaakov

and locally run by Aaronsohn's sister Sarah, they passed messages regarding Turkish troop maneuvers around the Haifa area.

In 1917 the Turks broke the spy ring. Sarah was arrested October 1, and after being tortured for three days, managed to

commit suicide. Most of the other members were captured and killed.

1916 May 16, SYKES-PICOT AGREEMENT

France and Britain (with the agreement of Russia) divided up the Ottoman Empire. France was assured of Lebanon, Syria

and Northern Iraq, and Britain was given control of Northern Arabia, Central Mesopotamia (Iraq), and much of the Western

Persian Gulf. Russia also received some Armenian and Kurdish territory. Eretz Israel was divided, with France controlling the

Galilee, Britain the Haifa area, and the rest of the country under international control.

1918 September 23, Haifa was captured by the Mysore and Jodhpur Lancers, British and Commonwealth troops. Many

soldiers are buried in Haifa cimetries

1920 January 4, METULLA (Eretz Israel)

Bedouin attacks on the north forced the French at a fort near Metulla to retreat. The 120 members of the settlement were

forced to flee to Sidon, where they boarded a ship to Haifa.

1925 February 10, THE TECHNION (The Israel Institute of Technology) (Eretz Israel)

Was opened in Haifa, making it the first institute of higher education to be opened in Eretz Israel. Its first head was Shlomo

Kaplansky whose goal was to train engineers to the highest of European standards. By 1952 the Technion was offering

Masters and Doctorates. Today the Technion remains Israel's main training center for its high tech industries.

1940 November 25, SINKING OF THE PATRIA (Haifa, Eretz Israel)

In Haifa harbor. The French refugee ship, the Patria carried 1,771 "illegal" immigrants. The British decided to add

otherillegals and deport them all to Mauritius, a British colony east of Madagascar. To prevent this move, members of the

Haganah decided to disable the ship. Unfortunately, the explosive charge was too large or the hull was too weak, and the ship

sunk, drowning 257 people. The survivors were allowed to remain in Eretz Israel and were interned for a while at the Athlit

detention camp near Haifa.

1940 June 10, ITALY DECLARED WAR ON GREAT BRITAIN AND FRANCE

A month later, the Italian air forces began bombing Haifa and Tel Aviv. Almost 200 people were killed with hundreds

wounded.

1941 June 12, LUFTWAFFE BOMBED TEL AVIV AND HAIFA (Eretz Israel)

Twelve people were killed in a Tel Aviv old age home.

1944 February 1, IRGUN ZVAI LEUMI (Eretz-Israel)

Began its revolt against British rule. The two limitations it set for itself was not to attack military targets until the end of the

war and not to attack individuals. On February 12, they attacked the British immigration offices in Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, and

Haifa.

1945 November 1, NIGHT OF THE RAILWAYS (Eretz Israel)

In the first cooperative effort between the Haganah, Etzel, and Lehi, railroad tracks all over the country were blown up. This

unification was known as Tnuat HaMeri HaIvri (The Hebrew (Jewish) Resistance Movement. The Haganah sabotaged

railway tracks in 153 places throughout the country, as well as targets in Jaffa and Haifa ports. The Irgun-Lehi unit,

commanded by Eitan Livni, attacked the main railway station at Lydda (Lod). The movement included two representatives of

the Haganah (Yisrael Galili and Moshe Sneh), an Irgun delegate (Menahem Begin) and a Lehi delegate (Nathan Yellin-Mor).

All operations were authorized by the Haganah command, which had the right of veto based on strategic, or political

considerations.

1947 March 31, HAIFA OIL REFINERY (Eretz Israel)

Was severely damaged by Lehi fighters.

1947 July 18, EXODUS 1947 (Eretz Israel)

Was towed to Haifa. The refugees were forced off the boat into three other boats. The Exodus (originally the President

Warfield) carried 4,500 survivors and was stopped at sea by the British Navy. During the struggle, a number of Jews were

killed. The Exodus was destined to become the symbol for all Jews prevented from being able to leave the slaughterhouse of

Europe and immigrate to Israel.

1947 December 29, HAIFA (Eretz Israel)

Arabs attacked Jewish workers at the oil refinery in Haifa, 39 were killed. Two days later, the Haganah attacked the village of

Balad a Sheich in a retaliatory raid.

1948 April 23, HAIFA CAPTURED (Eretz Israel)

By the Haganah. Although loudspeakers called on the Arabs to stay, they fled in mass, urged to do so by leaders of the Arab

High Command. Many of these leaders believed that the upcoming war would be helped by masses of Arab refugees whose

presence would encourage them to join in the attack. The refugees were promised that they would only be away for a short

time and would be able to return when the attacking armies "drive the Jews into the sea". They were also promised

compensation for their property.

1948 April 28, IRGUN ATTACKED HAIFA (Eretz Israel)

After its initial success at capturing the Menasiya quarter, the British prevented the Irgun from continuing. At the same time

the Haganah began Operation Chometz (unleavened bread) to take the areas around the city.

1103 Acre conquered by the Crusaders

Marco Polo was in Acco on his way

from Venice to Kublai Khan,

from Venice to Kublai Khan,

Zebulon, Marc Chagall,

Rejoice, O Zebulon, on your journeys,

And Issachar, in your tents.

They invite their kin to the mountain,

Where they offer their sacrifice of success.

For they draw from the riches of the sea

And the hidden riches of the sand

Mose's blessing, Deuteronomy 33

And Issachar, in your tents.

They invite their kin to the mountain,

Where they offer their sacrifice of success.

For they draw from the riches of the sea

And the hidden riches of the sand

Mose's blessing, Deuteronomy 33

Biblical times

Murex trunculus,

Argamnan-purple

Argamnan-purple

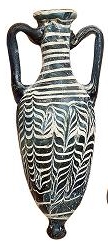

Glass Hecht museum

Glass President's home

The discovery of glass, related by Pline, Natural History, Chapter XXXVI

Phoenician sailors coming from Egypt landed on the shore, next to the Belus

(Naaman) river. They prepared some food on the shore using lumps of natron to

heat their pots. To their astonishment they saw that the natron had combined with

the salt to form a new clear and transparent material, glass.

Phoenician sailors coming from Egypt landed on the shore, next to the Belus

(Naaman) river. They prepared some food on the shore using lumps of natron to

heat their pots. To their astonishment they saw that the natron had combined with

the salt to form a new clear and transparent material, glass.

???????????????????????????????????????????????

in the past today

your journeys the port the port

the riches of the sea purple dye natural gas

hidden riches of the sand glass silicon wafers

???????????????????????????????????????????????

in the past today

your journeys the port the port

the riches of the sea purple dye natural gas

hidden riches of the sand glass silicon wafers

???????????????????????????????????????????????

Tancrede, prince of Tiberias (?-1112)

by Merry Joseph Blondel

Versailles (crusades Hall)

by Merry Joseph Blondel

Versailles (crusades Hall)

Electric plant, 1925, architect Erich Mendelssohn

Leopolf Krakauer, Hotel Teltash, Merkaz Carmel

Inauguration of the Hedjaz railway

Tintin in Haifa

Herge

Herge

Model of crusaders boat

National Maritime Museum

National Maritime Museum

Tel Shikmona, byzanttine 6th century

In 1492, Sultan Bayezid II sent the Ottoman navy under the command of Kemal

Reis to save the Arabs and Jews who were expelled from Spain and welcomed

them mainly in Saloniki and Constantinople.

The Mamelukes were defeated by Selim I at Ridaniya and Syria, Palestine and

Egypt became parts of the Ottoman Empire

Suleiman the Magnificient protected his Jewish subjects On the suggestion of

his physician Moses Hamon, the Sultan issued a firman formally denouncing

blood libels against the Jews. He also rented Tiberias to Dona Gracia Nasi and

later Tiberias and Safed to his nephew Joseph Nasi, duke of Naxos. Dona Gracia

hoped to create there a country for persecuted Jews

Reis to save the Arabs and Jews who were expelled from Spain and welcomed

them mainly in Saloniki and Constantinople.

The Mamelukes were defeated by Selim I at Ridaniya and Syria, Palestine and

Egypt became parts of the Ottoman Empire

Suleiman the Magnificient protected his Jewish subjects On the suggestion of

his physician Moses Hamon, the Sultan issued a firman formally denouncing

blood libels against the Jews. He also rented Tiberias to Dona Gracia Nasi and

later Tiberias and Safed to his nephew Joseph Nasi, duke of Naxos. Dona Gracia

hoped to create there a country for persecuted Jews

Beyazet II

Selim I

Suleiman the Magnificient

Kemal Reis boat

La Senora et Joseph Nasi

On His Majesty's Service:

the Story of Haifa during the British

Mandate Period 1918-1947

at the Haifa City Museum

the Story of Haifa during the British

Mandate Period 1918-1947

at the Haifa City Museum

Technicum (1912)

Guy Galazka

À la Redécouverte de la Palestine :

Le Regard sur l’Autre dans les récits de voyage

français en Terre sainte au dix-neuvième siècle

These Universite Paris Sorbonne 2010

À la Redécouverte de la Palestine :

Le Regard sur l’Autre dans les récits de voyage

français en Terre sainte au dix-neuvième siècle

These Universite Paris Sorbonne 2010

Léonie de Bazelaire, Haifa and the Carmel, 1899 (BNF)

Port in a storm

by Shay Fogelman

from Haaretz 3/6/11

The mass flight of Haifa's Arabs remains one of the

most contested events of the 1948 war. Yet despite

strong evidence to support Arab claims, Israeli

historians remain economical with the truth. Here's

the story they don't want you to know.

By Shay Fogelman

Two months ago, the Knesset passed the Budget

Principles Law (Amendment 39 ), more popularly

known as the "Nakba Law." The ostensibly

procedural clause is intended to prevent institutions

that receive state funding from marking the "day of

the catastrophe" - which is how the Palestinians

refer to May 15, 1948, the day the British Mandate in

Palestine came to an end.

Paradoxically, it is the determined attempt to erase

the day from the Israeli-Jewish consciousness that

has increased awareness of the Nakba among Jews.

Recent months saw a surge in Internet searches for

the word "Nakba," according to Google Trends

(which shows word-search patterns on the Web ).

The index shows the usual yearly leap in English and

Arabic ahead of May, but indicates an

unprecedentedly huge increase in Hebrew this year.

Clearly, the unusually large scope of events on

Nakba Day last month contributed to the growing

public interest and heightened the emotional content

of the term - sometimes absurdly so. Two weeks ago,

for example, MK Aryeh Eldad (National Union )

objected to the decision to hang a painting titled "The

Citrus Grower" in the Knesset building. According to

Eldad, the work is a "Nakba painting." The painting,

by Eliyahu Arik Bokobza, is based on a pastoral

photograph taken in 1939, showing a rural Arab

family dressed in traditional garb, with orange trees

in the background. In his complaint to the Knesset

speaker, Eldad wrote, "Why do you want to add an

artistic expression by an Israeli artist with a twisted

mind and afflicted by self-hate, who is calling the

Arab lie the truth and thereby rejecting our truth?"

This year, the primal fear of the Nakba spurred an

"appropriate Zionist response." Since Independence

Day, members of Im Tirtzu - an ultra-nationalist

group - have been distributing a pamphlet called

"Nakba Nonsense - The Pamphlet that Fights for the

Truth." In the course of 70 pages, the authors -

journalist Erel Segal and Im Tirtzu co-founder Erez

Tadmor - try to persuade readers that the Arabs, who

view themselves as victims of the Israeli-Palestinian

conflict, are actually the aggressors. It therefore

follows that Israel, which is generally perceived as

the aggressor, is actually the victim. In their words,

the pamphlet "tries to fight the lies, and it prosecutes

a war against the terrible falsehoods in whose name

our enemies seek to undermine the just path of

Zionism and prepare the ground for the destruction

of the Jewish state." The authors refer to the

succession of lies they say they are refuting as "the

myth of the Nakba."

In the pamphlet's second chapter, titled "The

Abandonment - Haifa as a Case in Point," the

authors discuss what they call the lie of the

"deliberate expulsion." Drawing on the book

"Fabricating Israeli History" by Prof. Efraim Karsh,

they proceed to take issue with the so-called "new

historians" - academics who question the

conventionally-held Arab-Israeli narrative. According

to the pamphlet, these academics are out "to spread

the libel that the Jewish fighting forces perpetrated a

series of brutal massacres in the service of a

deliberate policy of expulsion and ethnic cleansing."

The authors conclude the chapter by describing the

conquest of Haifa in the War of Independence as

evidence that the Israeli side did not pursue any such

policy and that "the Arab leadership bears

responsibility for the results of the war and the

refugee problem."

It is not by chance that the authors chose the

example of Haifa's capture in April 1948 by the

Haganah (the pre-independence army of Palestine's

Jews ), to rest their case. The events in Haifa are

considered perhaps the most treacherous minefield in

the history of the Nakba. Nearly every historian who

has researched the period, or the Israeli-Palestinian

conflict, has tried to navigate his way through this

field. Few have succeeded in reaching a firm

conclusion without stumbling on one of the mines of

mistaken interpretation. Many scholars have claimed

that their predecessors failed to make it through.

Despite a plethora of testimonies, documents and

studies, the historical controversy has yet to be

decided, and in the public debate each side often

resorts to the case of Haifa to strengthen its case.

The facts and testimonies that Segal and Tadmor cite

in their pamphlet are not new, nor do they contradict

facts and data that have appeared in earlier works on

the subject. But in the best tradition of political

pamphleteering, they are presented selectively and

one-sidedly, in order to support a predetermined

narrative. Neither the pamphlet nor, still less, the

chapter on Haifa, offer a true discussion or a

balanced presentation of facts.

Segal and Tadmor traverse the Haifa Nakba

minefield by means of leaps and bounds, refraining

from dealing with facts or testimonies that might

undermine the thesis they are propounding. In an era

dominated by "narratives," in which "truth" is

considered relative, the method used by the authors

to choose their sources might even be considered

legitimate; in the Israel of 2011, it is certainly also

legal.

"Even though the pamphlet is not an academic

study, I consulted with many academics while

working on it," Tadmor says, in a telephone

interview. "I chose to present the findings of Prof.

Karsh and of other historians, such as Benny Morris,

because they seemed to me to be reliable." Segal too

maintains that the pamphlet "does not purport to be

an academic study. Each side is able to choose the

studies it finds suitable. In the same way that

Palestinian propaganda chooses to relate certain

things it finds convenient, we chose to tell our truth.

I accept Prof. Karsh's study as scientific and

reliable."

The flight from Haifa

History cannot be treated as propaganda in the

old-timer's club in Haifa's Wadi Nisnas

neighborhood. For the dozens of local Arab residents

who visit the club every day, the Nakba is a chapter

in their personal biography. One of them remembers

how Jewish troops expelled his neighbors at

gunpoint; another describes how Haganah snipers

shot at his father as he returned home from work; a

third recalls the small bundle he carried while

fleeing. All of them remember the fear they felt as

helpless civilians, caught in the storm of war.

The stories they tell are on a minor scale. They

describe small moments: Looks they encountered,

experiences of defeat, humiliation and, occasionally,

arbitrary abuse by Haganah fighters. Some of them

spice their personal tragedy with humor, though the

sadness in their eyes remains constant. The years

have blunted the memory of all of them. In some

cases the stories get mixed up and details from later

periods are added.

By most estimates, 62,500 Arabs called Haifa their

home before the War of Independence. Under the

United Nations partition plan, they were to live in a

mixed city as citizens of the Jewish state after the

expiry of the British Mandate. However, rising

tensions between the sides and a series of mutual acts

of hostility prompted many Arabs to leave the city in

the weeks before the British departed. Most of the

leavers were affluent and many of them were

Christians who were given aid and shelter by

churches in the Galilee. By mid-April 1948, fewer

than 20,000 Arabs remained in the city.

Like the Jewish residents, they too waited to see how

things would develop. In the meantime they tried to

maintain as normal a life as possible amid the

violence. "Life in the city became intolerable at that

time," recalls Jamal Jaris, 90, in the Wadi Nisnas

club, as he tries to explain why he fled the city a few

days before it fell to the Jewish forces. "There were

shots and bombs every day. No distinction was made

between civilians and armed combatants. In certain

parts of the city, especially in the Arab

neighborhoods, everyone who walked in the street

was exposed to snipers and machine guns."

On April 21, the commander of the British forces in

Haifa informed both sides that his troops were

evacuating the city immediately, apart from the

harbor and a few key roads that the army would need

during the organized withdrawal in mid-May. That

same night the Haganah launched an attack on the

Arab neighborhoods. The Carmeli Brigade, which

spearheaded the assault, enjoyed numerical and

topographical superiority. Its troops were also better

trained and better equipped and fought in a far more

organized manner than the Arab forces. In less than

a day, all of Haifa fell to the Haganah.

Indiscriminate shooting

It was a short battle and a crushing victory, in which

the Jewish side sustained relatively few casualties.

The Arabs put up only minor resistance. Haganah

troops who searched the Arab neighborhoods after

the battle were surprised to find so few weapons. A

week later, the Haganah journal Ma'arakhot

(Campaigns ) wrote, "The battle of Haifa will

perhaps not be counted among the great city battles

in military history."

However, the Jewish victory spurred the panicky

flight of most of the city's remaining residents.

"Haifa, third largest city of Palestine and evacuation

port of the British Army, became a virtual Jewish

stronghold tonight after a series of savage thrusts by

Haganah, the Jewish army, won control of most of

the city's Arab areas and provoked a mass Arab

exodus by sea," the New York Herald Tribune

reported. On April 23 the New York Times wrote:

"Tens of thousands of Arab men, women and

children fled toward the eastern outskirts of the city

in cars, trucks, carts and afoot, in a desperate

attempt to reach Arab territory until the Jews

captured Rushmiya Bridge toward Samaria and

Northern Palestine and cut them off. Thousands

rushed every available craft, even rowboats, along

the waterfront, to escape by sea toward Acre."

The Israeli newspaper Ma'ariv wrote, "British

harbor officials estimate that 12,000 to 14,000 Arabs

left by sea and 2,000 to 4,000 by land. The Jewish

and Arab numbers contradict one another. The Jews

are trying to reduce the scale of the exodus. An

official Jewish spokesman said that no more than

5,000 Arabs left. However, Arab leaders said that at

least 20,000 left."

"We were afraid." That is the sole explanation -

offered by another frequenter of the old-timers' club,

85-year-old Chana Mur - for the flight of the city's

Arab residents. On the day the city was conquered, he

says, he went to work as usual in the port's customs

division: "For hours we heard explosions and

gunfire from the direction of the Arab

neighborhoods. The Jews shot at the houses and

sniped at people in the streets. There was a huge

panic. I remember people saying they felt the world

was turning upside down. The port remained the

only safe place for Arabs. They were protected there

by the British soldiers. Whoever was able collected a

few things in a blanket or a knapsack and fled to the

port. Our feeling was that we were running for our

lives.

"I remember a young couple who, in the panic of

fleeing, forgot their little daughter at home," Mur

continues. "They probably took some other bundle

instead of her. She was found by the neighbor on the

second floor. He heard her crying when he fled and

took her with his family. Her parents eventually

reached a refugee camp in Lebanon, and the girl was

raised at [the neighbor's] home in Acre. I later met

her; she now lives in the village of Kababir in Haifa."

Several history books published in Israel in recent

years describe the flight of thousands of Haifa Arabs

to the port on the day of the city's conquest, and their

departure by sea to Acre and Lebanon. The event

assumes greater import and significance in the

newspapers of the time and in various archives.

Segal and Tadmor write: "On April 22, as Haganah

forces moved toward the market, a mass flight of

thousands was recorded." They do not say what

happened in the market, preferring instead to draw

on Prof. Karsh's thesis. "The Arab leadership," they

write, "urged the members of their nation to

evacuate their homes, whether to clear the territory

for the Arab forces or for propaganda purposes

aimed at negating the legitimacy of the Jewish state."

Another source the authors cite for their chapter

conclusions is the book by historian Benny Morris,

"1948," (published in English in 2008 and two years

later in Hebrew ). They write that Morris used to be a

new historian "until he recanted," and add that he is

the most respected and serious member of the group.

Morris has written about the Haifa conquest and

mentioned the flight of the Arab residents to the port

in several studies. In "1948," he describes the events

of April 22 as follows: "The constant mortar and

machine gun fire, as well as the collapse of the

militias and local government and the Haganah's

conquests, precipitated mass flight toward the

British-held port area. By 1:00 P.M. some 6,000

people had reportedly passed through the harbor and

boarded boats for Acre and points north."

Morris sums up the reasons for the flight with these

words: "The majority had left for a variety of

reasons, the main one being the shock of battle

(especially the Haganah mortaring of the Lower City

) and Jewish conquest and the prospect of life as a

minority under Jewish rule." However, in his first

book, "The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee

Problem" (first English-language edition, 1987 ),

which was written well before his "recantation,"

Morris described the course of events in greater detail

and shed a different light on them, quoting from a

book by an Israeli historian: "The three-inch mortars

'opened up on the market square [where there was] a

great crowd ... a great panic took hold. The multitude

burst into the port, pushed aside the policemen,

stormed the boats and began fleeing the town.'"

But this, too, is very much a partial description.

Morris actually quotes from a book by Zadok Eshel,

"Haganah Battles in Haifa," published in 1978 (in

Hebrew ) by the Defense Ministry. Eshel was a

member of the Haganah and offers first-hand

descriptions of many of the unfolding events in

Haifa. Here is his account of the events of April 22

(note the words which Morris omitted and replaced

by an ellipsis ): "Early in the morning, Maxy Cohen

informed the brigade's headquarters that the Arabs

were using a loudspeaker and calling on everyone to

gather in the market square, 'because the Jews have

conquered Stanton Street and are continuing to make

their way downtown.' Upon receiving the report, an

order was given to the commander of the auxiliary

weapons company, Ehud Almog, to make use of the

three-inch mortars, which were situated next to

Rothschild Hospital, and they opened up on the

market square [where there was] a great crowd.

When the shelling started and shells fell into it [the

crowd], a great panic took hold. The multitude burst

into the port, pushed aside the policemen, stormed

the boats and began fleeing the town. Throughout

the day the mortars continued to shell the city

alternately, and the panic that seized the enemy

became a rout."

"That is a mistake," retorts Ehud Almog, who was

the commander of the auxiliary unit in the Carmeli

Brigade's 22nd Battalion. "It was not a three-inch

mortar. They were Davidka shells" - referring to

homemade shells which were renowned for the loud

noise they made. Of the other details he says, "The

historical description is correct. Absolutely true. I

remember the events vividly. We were ordered to

shell the market when there was a large crowd there.

There were tremendous noises of explosions which

were heard across 200 meters." Almog adds that the

shelling, which took place in the early afternoon, was

short "but very effective."

Like Eshel, Almog also says the mortars fired by his

unit spurred a flight of civilians to the port. Although

not an eyewitness to the flight, officers from Shai

(the Haganah's intelligence unit ) who were stationed

near the port's gates gave him a real-time account of

events. Another testimony (quoted by Morris in "The

Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem" ) comes

from a British soldier who was stationed in the port:

"During the morning they [the Haganah] were

continually shooting down on all Arabs who moved

both in Wadi Nisnas and in the Old City. This

included completely indiscriminate and revolting

machine gun fire and sniping on women and

children - attempting to get out of Haifa through the

gates into the docks. There was considerable

congestion outside the East Gate [of the port] of

hysterical and terrified Arab women and children

and old people on whom the Jews opened up

mercilessly with fire." (A truncated version of this

quote also appears in "1948" - reduced to

"completely indiscriminate and revolting ... fire," the

ellipsis replacing the words "machine gun." )

Beyond the moral issues that arise from firing into a

crowded market, the testimony of Zadok Eshel,

which is backed up by that of Ehud Almog, indicates

that the attack was carried out by order of senior

Haganah officers. How senior they were is not

known. Not all the Israel Defense Forces archival

material about this period is accessible to the public.

It is therefore impossible to determine whether the

shelling was part of a general policy aimed at

expelling the Arabs, or one of several similar

instances that were documented during the war.

Bodies in the streets

The shelling took place as Arab representatives were

holding negotiations with Haifa's Jewish leaders on

the terms for a ceasefire. Most of the testimonies

from the time suggest that the city's mayor, Shabtai

Levy, believed in coexistence. Many studies note that

he urged the Arabs to capitulate and remain in the

city. At certain moments this actually seemed

possible. A correspondent for United Press

Associations (UP) reported that, even though nothing

official had been said, it appeared certain that the

conditions laid down by the Jews had been accepted

by the Arabs, at least in the main. Reportedly, the

Arab Legion and the Iraqi volunteers had already

begun to leave the city.

However, Haganah headquarters operated

independently; even as senior officers kept abreast of

the progress of the ceasefire talks, their forces

continued to fire on Arab neighborhoods. A cable

from Carmeli Brigade to Haganah headquarters at

2:30 P.M. on the day of the battle stated, "Arabs in

Haifa approached the general, the mayor, seeking a

mediator between them and the Haganah, to accept

the ceasefire terms." A copy of the agreement in

English, as drawn up by the Haganah, was appended

to the cable. The cable concluded, "Panic, flight

among the Arabs. Resistance very feeble."

The Haganah mortars harassed the fleeing Arabs.

According to the Jewish force's daily events sheet,

the duty officer announced at 2:40 P.M.: "Three

shells landed next to the gate of Port No.3. The shells

are coming from the direction of the city's Hadar

Carmel section [i.e. from higher ground, on Mount

Carmel]. Similar case occurred this morning and the

[British] Army is threatening to attack Hadar with

artillery if this does not stop." In other cases, the

British Army opened fire and scored hits on

Haganah soldiers who had shot at Arab civilians.

At 3 P.M. the text of the agreement was resent, with

several corrections inserted by the English general.

Moshe Carmel, the brigade commander, reported to

Haganah headquarters, "A joint meeting of Jews,

English and Arabs will be held at 4 P.M. [today] to

discuss the terms. We can assume that the Arabs will

not accept them, because technically there is no

possibility of an organized surrender." Haganah

headquarters responded, "As long as it is not certain

the terms will be met, you must go on attacking."

The message concluded: "Be especially careful of a

trap, in case the negotiations are [intended] to gain

time."

At 4 P.M., under the mediation of British officers,

the two sides began to discuss the surrender and

ceasefire terms. The Arabs requested more time for

consultations. The sides met again at 7:15 P.M. The

Haganah report stated, "The Arabs claimed they

cannot fulfill the terms. Because the Arabs will not

obey them [sic], they prefer to evacuate the city of

Haifa completely of its Arab residents." A Haganah

intelligence report from the day of the battle relates,

"There are signs that the Arab command in the city

is falling apart. Arab headquarters have been

abandoned. No one is answering the phone and there

are reports that the commanders and their staff have

abandoned Haifa. Exact numbers of enemy losses

are unknown. The Arab hospitals are known to be

filled with dead and wounded. Bodies of the dead lie

in the streets, along with the wounded, and are not

being collected because of disorganization and lack

of hygienic means. There is great panic among the

Arabs. They are waiting for an armistice to be signed

and for the Jews to take over as a good development

which will be their salvation. In the meantime, a

report was received from an Arab source that they

have accepted our armistice terms."

Silence of the historians

In the Palestinians' consciousness, the shelling of the

crowded market in Haifa occupies a significant place

in the history of the Nakba in the city. Sitting in the

old-timers' club in Wadi Nisnas, Awda al-Shehab,

87, says the shelling "had a great influence on the

flight to the port. People gathered in the market to

discuss the situation and the terms being proposed

for a ceasefire. Historians tell us now that the

[Jewish] mayor wanted the Arabs to stay and that

after the war the Haganah did all it could to prevent

the departure, but acts are far more weighty than

words. And when the mortar shells landed in the

heart of the market, the Arabs took this as the Jewish

response to the ceasefire proposal."

Similar claims were made 63 years ago. According to

a UP report which appeared in Davar (the newspaper

of the Histadrut labor federation ), the Arabs

maintained that Jews had "violated the armistice in

Haifa" and had created a "new wave of panic

among thousands of Arabs" who were rushing to

leave the city. Privately, the report continued, Jews

admitted that during the battle and for some time

afterward people lost their heads and there was some

looting and shooting at civilians.

Over the years, some Israeli researchers tried to play

down the significance of the shelling of the market.

In his 2006 book "Palestine 1948: War, Escape and

the Emergence of the Palestinian Refugee Problem,"

Prof. Yoav Gelber writes, "After several mortar

shells fell in the vicinity of the market, where large

numbers of Arabs had gathered, masses of people

stormed the port, driven by fear of the gunfire and

shelling." However, Zadok Eshel says explicitly that

the shells landed within the crowd. Gelber does not

explain how he arrived at the conclusion that the

shells struck only "the vicinity of the market."

Gelber also ignores the testimonies of dozens of

wounded Arabs who remained in the market after

the mass flight. Most of the Palestinian researchers

estimate that "several dozen were killed." Haaretz

reported after the battle that "a member of the Arab

National Committee said that the Jews had killed a

large number of women and children who had tried

to flee to the Old City, to the British security zone in

the port ... Although the Jews denied the reports of

heavy losses supposedly inflicted on Arab civilians,

the Haganah spokesman said, 'Even if that is what

happened, we are not to blame, as we broadcast over

the radio and over loudspeakers 48 hours before our

attack a warning in Arabic, which we also distributed

via leaflets, calling on the Arabs to evacuate the

women and children and send everyone who is not

from Haifa out of the city. We repeated that this

would be our final warning."

"An appalling and fantastic sight," David

Ben-Gurion wrote in his diary after visiting the city's

abandoned Arab neighborhoods on May 1. "A dead

city, a carcass city ... without a living soul, apart

from stray cats." The empty streets were strewn with

dozens of bodies of Arab civilians. Red Crescent units

that collected them initially estimated their number at

more than 150; three days later, they revised the

estimate downward to 80 Arabs who were killed in

the battles and several hundred wounded. According

to the Red Crescent, only six of those killed were

combatants and the majority of the bodies were of

women and children.

Many bodies remained in the area of the shelled

market. A Haganah intelligence report relates that at

least ten bodies were found in the Ajami Cafe there.

They were removed only after all the unexploded

shells in the area were neutralized. The report added:

"It is hard to know the number of losses as a result

of the explosion on Nazareth Street in the house of

Abu Madi, as not all the bodies have as yet been

removed from the rubble. The house was packed

with families who moved there from outlying areas."

A few dozen Arab refugees remained in the port,

waiting on the docks for boats to rescue them, fearful

of returning to their homes. "The scenes in the port

were pitiful," Davar reported. "Women and children

were without food and water for the past two days.

The British say they cannot help very much, while

the Arabs maintain that this is a deliberate step by

the British in order to force the Arabs to return to

their homes."

In our conversation, the Arab old-timers in the Wadi

Nisnas club often mention "coexistence" and "a

state for two nations." They take great pride in the

deep, friendly relations they maintain with their

Jewish neighbors; a few of them say they have been

involved over the years in attempts to draw Jews and

Arabs closer together. From their viewpoint, the

Nakba is a historical fact which needs no

confirmation or legislation. Nor, in their view, need

it frighten or threaten the Jewish presence in the

country. As Awda al-Shehab says, "Only after we

recognize mutually the suffering that was endured by

the two peoples will we be able to create a common

future. That is the true key to coexistence. Without it,

each side will continue to live in the past."

by Shay Fogelman

from Haaretz 3/6/11

The mass flight of Haifa's Arabs remains one of the

most contested events of the 1948 war. Yet despite

strong evidence to support Arab claims, Israeli

historians remain economical with the truth. Here's

the story they don't want you to know.

By Shay Fogelman

Two months ago, the Knesset passed the Budget

Principles Law (Amendment 39 ), more popularly

known as the "Nakba Law." The ostensibly

procedural clause is intended to prevent institutions

that receive state funding from marking the "day of

the catastrophe" - which is how the Palestinians

refer to May 15, 1948, the day the British Mandate in

Palestine came to an end.

Paradoxically, it is the determined attempt to erase

the day from the Israeli-Jewish consciousness that

has increased awareness of the Nakba among Jews.

Recent months saw a surge in Internet searches for

the word "Nakba," according to Google Trends

(which shows word-search patterns on the Web ).

The index shows the usual yearly leap in English and

Arabic ahead of May, but indicates an

unprecedentedly huge increase in Hebrew this year.

Clearly, the unusually large scope of events on

Nakba Day last month contributed to the growing

public interest and heightened the emotional content

of the term - sometimes absurdly so. Two weeks ago,

for example, MK Aryeh Eldad (National Union )

objected to the decision to hang a painting titled "The

Citrus Grower" in the Knesset building. According to

Eldad, the work is a "Nakba painting." The painting,

by Eliyahu Arik Bokobza, is based on a pastoral

photograph taken in 1939, showing a rural Arab

family dressed in traditional garb, with orange trees

in the background. In his complaint to the Knesset

speaker, Eldad wrote, "Why do you want to add an

artistic expression by an Israeli artist with a twisted

mind and afflicted by self-hate, who is calling the

Arab lie the truth and thereby rejecting our truth?"

This year, the primal fear of the Nakba spurred an

"appropriate Zionist response." Since Independence

Day, members of Im Tirtzu - an ultra-nationalist

group - have been distributing a pamphlet called

"Nakba Nonsense - The Pamphlet that Fights for the

Truth." In the course of 70 pages, the authors -

journalist Erel Segal and Im Tirtzu co-founder Erez

Tadmor - try to persuade readers that the Arabs, who

view themselves as victims of the Israeli-Palestinian

conflict, are actually the aggressors. It therefore

follows that Israel, which is generally perceived as

the aggressor, is actually the victim. In their words,

the pamphlet "tries to fight the lies, and it prosecutes

a war against the terrible falsehoods in whose name

our enemies seek to undermine the just path of

Zionism and prepare the ground for the destruction

of the Jewish state." The authors refer to the

succession of lies they say they are refuting as "the

myth of the Nakba."

In the pamphlet's second chapter, titled "The

Abandonment - Haifa as a Case in Point," the

authors discuss what they call the lie of the

"deliberate expulsion." Drawing on the book

"Fabricating Israeli History" by Prof. Efraim Karsh,

they proceed to take issue with the so-called "new

historians" - academics who question the

conventionally-held Arab-Israeli narrative. According

to the pamphlet, these academics are out "to spread

the libel that the Jewish fighting forces perpetrated a

series of brutal massacres in the service of a

deliberate policy of expulsion and ethnic cleansing."

The authors conclude the chapter by describing the

conquest of Haifa in the War of Independence as

evidence that the Israeli side did not pursue any such

policy and that "the Arab leadership bears

responsibility for the results of the war and the

refugee problem."

It is not by chance that the authors chose the

example of Haifa's capture in April 1948 by the

Haganah (the pre-independence army of Palestine's

Jews ), to rest their case. The events in Haifa are

considered perhaps the most treacherous minefield in

the history of the Nakba. Nearly every historian who

has researched the period, or the Israeli-Palestinian

conflict, has tried to navigate his way through this

field. Few have succeeded in reaching a firm

conclusion without stumbling on one of the mines of

mistaken interpretation. Many scholars have claimed

that their predecessors failed to make it through.

Despite a plethora of testimonies, documents and

studies, the historical controversy has yet to be

decided, and in the public debate each side often

resorts to the case of Haifa to strengthen its case.

The facts and testimonies that Segal and Tadmor cite

in their pamphlet are not new, nor do they contradict

facts and data that have appeared in earlier works on

the subject. But in the best tradition of political

pamphleteering, they are presented selectively and

one-sidedly, in order to support a predetermined

narrative. Neither the pamphlet nor, still less, the

chapter on Haifa, offer a true discussion or a

balanced presentation of facts.

Segal and Tadmor traverse the Haifa Nakba

minefield by means of leaps and bounds, refraining

from dealing with facts or testimonies that might

undermine the thesis they are propounding. In an era

dominated by "narratives," in which "truth" is

considered relative, the method used by the authors

to choose their sources might even be considered

legitimate; in the Israel of 2011, it is certainly also

legal.

"Even though the pamphlet is not an academic

study, I consulted with many academics while

working on it," Tadmor says, in a telephone

interview. "I chose to present the findings of Prof.

Karsh and of other historians, such as Benny Morris,

because they seemed to me to be reliable." Segal too

maintains that the pamphlet "does not purport to be

an academic study. Each side is able to choose the

studies it finds suitable. In the same way that

Palestinian propaganda chooses to relate certain

things it finds convenient, we chose to tell our truth.

I accept Prof. Karsh's study as scientific and

reliable."

The flight from Haifa

History cannot be treated as propaganda in the

old-timer's club in Haifa's Wadi Nisnas

neighborhood. For the dozens of local Arab residents

who visit the club every day, the Nakba is a chapter

in their personal biography. One of them remembers

how Jewish troops expelled his neighbors at

gunpoint; another describes how Haganah snipers

shot at his father as he returned home from work; a

third recalls the small bundle he carried while

fleeing. All of them remember the fear they felt as

helpless civilians, caught in the storm of war.

The stories they tell are on a minor scale. They

describe small moments: Looks they encountered,

experiences of defeat, humiliation and, occasionally,

arbitrary abuse by Haganah fighters. Some of them

spice their personal tragedy with humor, though the

sadness in their eyes remains constant. The years

have blunted the memory of all of them. In some

cases the stories get mixed up and details from later

periods are added.

By most estimates, 62,500 Arabs called Haifa their

home before the War of Independence. Under the

United Nations partition plan, they were to live in a

mixed city as citizens of the Jewish state after the

expiry of the British Mandate. However, rising

tensions between the sides and a series of mutual acts

of hostility prompted many Arabs to leave the city in

the weeks before the British departed. Most of the

leavers were affluent and many of them were

Christians who were given aid and shelter by

churches in the Galilee. By mid-April 1948, fewer

than 20,000 Arabs remained in the city.

Like the Jewish residents, they too waited to see how

things would develop. In the meantime they tried to

maintain as normal a life as possible amid the

violence. "Life in the city became intolerable at that

time," recalls Jamal Jaris, 90, in the Wadi Nisnas

club, as he tries to explain why he fled the city a few

days before it fell to the Jewish forces. "There were

shots and bombs every day. No distinction was made

between civilians and armed combatants. In certain

parts of the city, especially in the Arab

neighborhoods, everyone who walked in the street

was exposed to snipers and machine guns."

On April 21, the commander of the British forces in

Haifa informed both sides that his troops were

evacuating the city immediately, apart from the

harbor and a few key roads that the army would need

during the organized withdrawal in mid-May. That

same night the Haganah launched an attack on the

Arab neighborhoods. The Carmeli Brigade, which

spearheaded the assault, enjoyed numerical and

topographical superiority. Its troops were also better

trained and better equipped and fought in a far more

organized manner than the Arab forces. In less than

a day, all of Haifa fell to the Haganah.

Indiscriminate shooting

It was a short battle and a crushing victory, in which

the Jewish side sustained relatively few casualties.

The Arabs put up only minor resistance. Haganah

troops who searched the Arab neighborhoods after

the battle were surprised to find so few weapons. A

week later, the Haganah journal Ma'arakhot

(Campaigns ) wrote, "The battle of Haifa will

perhaps not be counted among the great city battles

in military history."

However, the Jewish victory spurred the panicky

flight of most of the city's remaining residents.

"Haifa, third largest city of Palestine and evacuation

port of the British Army, became a virtual Jewish

stronghold tonight after a series of savage thrusts by

Haganah, the Jewish army, won control of most of

the city's Arab areas and provoked a mass Arab

exodus by sea," the New York Herald Tribune

reported. On April 23 the New York Times wrote:

"Tens of thousands of Arab men, women and

children fled toward the eastern outskirts of the city

in cars, trucks, carts and afoot, in a desperate

attempt to reach Arab territory until the Jews

captured Rushmiya Bridge toward Samaria and

Northern Palestine and cut them off. Thousands

rushed every available craft, even rowboats, along

the waterfront, to escape by sea toward Acre."

The Israeli newspaper Ma'ariv wrote, "British

harbor officials estimate that 12,000 to 14,000 Arabs

left by sea and 2,000 to 4,000 by land. The Jewish

and Arab numbers contradict one another. The Jews

are trying to reduce the scale of the exodus. An

official Jewish spokesman said that no more than

5,000 Arabs left. However, Arab leaders said that at

least 20,000 left."

"We were afraid." That is the sole explanation -

offered by another frequenter of the old-timers' club,

85-year-old Chana Mur - for the flight of the city's

Arab residents. On the day the city was conquered, he

says, he went to work as usual in the port's customs

division: "For hours we heard explosions and

gunfire from the direction of the Arab

neighborhoods. The Jews shot at the houses and

sniped at people in the streets. There was a huge

panic. I remember people saying they felt the world

was turning upside down. The port remained the

only safe place for Arabs. They were protected there

by the British soldiers. Whoever was able collected a

few things in a blanket or a knapsack and fled to the

port. Our feeling was that we were running for our

lives.

"I remember a young couple who, in the panic of

fleeing, forgot their little daughter at home," Mur

continues. "They probably took some other bundle

instead of her. She was found by the neighbor on the

second floor. He heard her crying when he fled and

took her with his family. Her parents eventually

reached a refugee camp in Lebanon, and the girl was

raised at [the neighbor's] home in Acre. I later met

her; she now lives in the village of Kababir in Haifa."

Several history books published in Israel in recent

years describe the flight of thousands of Haifa Arabs

to the port on the day of the city's conquest, and their

departure by sea to Acre and Lebanon. The event

assumes greater import and significance in the

newspapers of the time and in various archives.

Segal and Tadmor write: "On April 22, as Haganah

forces moved toward the market, a mass flight of

thousands was recorded." They do not say what

happened in the market, preferring instead to draw

on Prof. Karsh's thesis. "The Arab leadership," they

write, "urged the members of their nation to

evacuate their homes, whether to clear the territory

for the Arab forces or for propaganda purposes

aimed at negating the legitimacy of the Jewish state."

Another source the authors cite for their chapter

conclusions is the book by historian Benny Morris,

"1948," (published in English in 2008 and two years

later in Hebrew ). They write that Morris used to be a

new historian "until he recanted," and add that he is

the most respected and serious member of the group.

Morris has written about the Haifa conquest and

mentioned the flight of the Arab residents to the port

in several studies. In "1948," he describes the events

of April 22 as follows: "The constant mortar and

machine gun fire, as well as the collapse of the

militias and local government and the Haganah's

conquests, precipitated mass flight toward the

British-held port area. By 1:00 P.M. some 6,000

people had reportedly passed through the harbor and

boarded boats for Acre and points north."

Morris sums up the reasons for the flight with these

words: "The majority had left for a variety of

reasons, the main one being the shock of battle

(especially the Haganah mortaring of the Lower City

) and Jewish conquest and the prospect of life as a

minority under Jewish rule." However, in his first

book, "The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee

Problem" (first English-language edition, 1987 ),

which was written well before his "recantation,"

Morris described the course of events in greater detail

and shed a different light on them, quoting from a

book by an Israeli historian: "The three-inch mortars

'opened up on the market square [where there was] a

great crowd ... a great panic took hold. The multitude

burst into the port, pushed aside the policemen,

stormed the boats and began fleeing the town.'"

But this, too, is very much a partial description.

Morris actually quotes from a book by Zadok Eshel,

"Haganah Battles in Haifa," published in 1978 (in

Hebrew ) by the Defense Ministry. Eshel was a

member of the Haganah and offers first-hand

descriptions of many of the unfolding events in

Haifa. Here is his account of the events of April 22

(note the words which Morris omitted and replaced

by an ellipsis ): "Early in the morning, Maxy Cohen

informed the brigade's headquarters that the Arabs

were using a loudspeaker and calling on everyone to

gather in the market square, 'because the Jews have

conquered Stanton Street and are continuing to make

their way downtown.' Upon receiving the report, an

order was given to the commander of the auxiliary

weapons company, Ehud Almog, to make use of the

three-inch mortars, which were situated next to

Rothschild Hospital, and they opened up on the

market square [where there was] a great crowd.

When the shelling started and shells fell into it [the

crowd], a great panic took hold. The multitude burst

into the port, pushed aside the policemen, stormed

the boats and began fleeing the town. Throughout

the day the mortars continued to shell the city

alternately, and the panic that seized the enemy

became a rout."

"That is a mistake," retorts Ehud Almog, who was

the commander of the auxiliary unit in the Carmeli

Brigade's 22nd Battalion. "It was not a three-inch

mortar. They were Davidka shells" - referring to

homemade shells which were renowned for the loud

noise they made. Of the other details he says, "The

historical description is correct. Absolutely true. I

remember the events vividly. We were ordered to

shell the market when there was a large crowd there.

There were tremendous noises of explosions which

were heard across 200 meters." Almog adds that the

shelling, which took place in the early afternoon, was

short "but very effective."

Like Eshel, Almog also says the mortars fired by his

unit spurred a flight of civilians to the port. Although

not an eyewitness to the flight, officers from Shai

(the Haganah's intelligence unit ) who were stationed

near the port's gates gave him a real-time account of

events. Another testimony (quoted by Morris in "The

Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem" ) comes

from a British soldier who was stationed in the port:

"During the morning they [the Haganah] were

continually shooting down on all Arabs who moved

both in Wadi Nisnas and in the Old City. This

included completely indiscriminate and revolting

machine gun fire and sniping on women and

children - attempting to get out of Haifa through the

gates into the docks. There was considerable

congestion outside the East Gate [of the port] of

hysterical and terrified Arab women and children

and old people on whom the Jews opened up

mercilessly with fire." (A truncated version of this

quote also appears in "1948" - reduced to

"completely indiscriminate and revolting ... fire," the

ellipsis replacing the words "machine gun." )

Beyond the moral issues that arise from firing into a

crowded market, the testimony of Zadok Eshel,

which is backed up by that of Ehud Almog, indicates

that the attack was carried out by order of senior

Haganah officers. How senior they were is not

known. Not all the Israel Defense Forces archival

material about this period is accessible to the public.

It is therefore impossible to determine whether the

shelling was part of a general policy aimed at

expelling the Arabs, or one of several similar

instances that were documented during the war.

Bodies in the streets

The shelling took place as Arab representatives were

holding negotiations with Haifa's Jewish leaders on

the terms for a ceasefire. Most of the testimonies

from the time suggest that the city's mayor, Shabtai

Levy, believed in coexistence. Many studies note that

he urged the Arabs to capitulate and remain in the

city. At certain moments this actually seemed

possible. A correspondent for United Press

Associations (UP) reported that, even though nothing

official had been said, it appeared certain that the

conditions laid down by the Jews had been accepted

by the Arabs, at least in the main. Reportedly, the

Arab Legion and the Iraqi volunteers had already

begun to leave the city.

However, Haganah headquarters operated

independently; even as senior officers kept abreast of

the progress of the ceasefire talks, their forces

continued to fire on Arab neighborhoods. A cable

from Carmeli Brigade to Haganah headquarters at

2:30 P.M. on the day of the battle stated, "Arabs in

Haifa approached the general, the mayor, seeking a

mediator between them and the Haganah, to accept

the ceasefire terms." A copy of the agreement in

English, as drawn up by the Haganah, was appended

to the cable. The cable concluded, "Panic, flight

among the Arabs. Resistance very feeble."

The Haganah mortars harassed the fleeing Arabs.

According to the Jewish force's daily events sheet,

the duty officer announced at 2:40 P.M.: "Three

shells landed next to the gate of Port No.3. The shells

are coming from the direction of the city's Hadar

Carmel section [i.e. from higher ground, on Mount

Carmel]. Similar case occurred this morning and the

[British] Army is threatening to attack Hadar with

artillery if this does not stop." In other cases, the

British Army opened fire and scored hits on

Haganah soldiers who had shot at Arab civilians.

At 3 P.M. the text of the agreement was resent, with

several corrections inserted by the English general.

Moshe Carmel, the brigade commander, reported to

Haganah headquarters, "A joint meeting of Jews,

English and Arabs will be held at 4 P.M. [today] to

discuss the terms. We can assume that the Arabs will

not accept them, because technically there is no

possibility of an organized surrender." Haganah

headquarters responded, "As long as it is not certain

the terms will be met, you must go on attacking."

The message concluded: "Be especially careful of a

trap, in case the negotiations are [intended] to gain

time."

At 4 P.M., under the mediation of British officers,

the two sides began to discuss the surrender and

ceasefire terms. The Arabs requested more time for

consultations. The sides met again at 7:15 P.M. The

Haganah report stated, "The Arabs claimed they

cannot fulfill the terms. Because the Arabs will not

obey them [sic], they prefer to evacuate the city of

Haifa completely of its Arab residents." A Haganah

intelligence report from the day of the battle relates,

"There are signs that the Arab command in the city

is falling apart. Arab headquarters have been

abandoned. No one is answering the phone and there

are reports that the commanders and their staff have

abandoned Haifa. Exact numbers of enemy losses

are unknown. The Arab hospitals are known to be

filled with dead and wounded. Bodies of the dead lie

in the streets, along with the wounded, and are not

being collected because of disorganization and lack

of hygienic means. There is great panic among the

Arabs. They are waiting for an armistice to be signed

and for the Jews to take over as a good development

which will be their salvation. In the meantime, a

report was received from an Arab source that they

have accepted our armistice terms."

Silence of the historians

In the Palestinians' consciousness, the shelling of the

crowded market in Haifa occupies a significant place

in the history of the Nakba in the city. Sitting in the

old-timers' club in Wadi Nisnas, Awda al-Shehab,

87, says the shelling "had a great influence on the

flight to the port. People gathered in the market to

discuss the situation and the terms being proposed

for a ceasefire. Historians tell us now that the

[Jewish] mayor wanted the Arabs to stay and that

after the war the Haganah did all it could to prevent

the departure, but acts are far more weighty than

words. And when the mortar shells landed in the

heart of the market, the Arabs took this as the Jewish

response to the ceasefire proposal."

Similar claims were made 63 years ago. According to

a UP report which appeared in Davar (the newspaper

of the Histadrut labor federation ), the Arabs

maintained that Jews had "violated the armistice in

Haifa" and had created a "new wave of panic

among thousands of Arabs" who were rushing to

leave the city. Privately, the report continued, Jews

admitted that during the battle and for some time

afterward people lost their heads and there was some

looting and shooting at civilians.

Over the years, some Israeli researchers tried to play

down the significance of the shelling of the market.

In his 2006 book "Palestine 1948: War, Escape and

the Emergence of the Palestinian Refugee Problem,"

Prof. Yoav Gelber writes, "After several mortar

shells fell in the vicinity of the market, where large

numbers of Arabs had gathered, masses of people

stormed the port, driven by fear of the gunfire and

shelling." However, Zadok Eshel says explicitly that

the shells landed within the crowd. Gelber does not

explain how he arrived at the conclusion that the

shells struck only "the vicinity of the market."

Gelber also ignores the testimonies of dozens of

wounded Arabs who remained in the market after

the mass flight. Most of the Palestinian researchers

estimate that "several dozen were killed." Haaretz

reported after the battle that "a member of the Arab

National Committee said that the Jews had killed a

large number of women and children who had tried

to flee to the Old City, to the British security zone in

the port ... Although the Jews denied the reports of

heavy losses supposedly inflicted on Arab civilians,

the Haganah spokesman said, 'Even if that is what

happened, we are not to blame, as we broadcast over